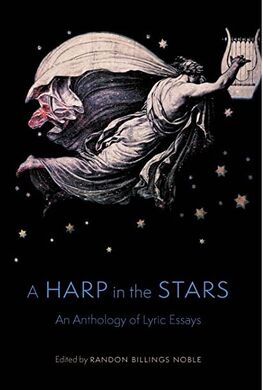

Anthologies

The Harp in the Stars, an Anthology of Lyric Essays

Edited by Randon Billings Noble

University of Nebraska Press, October 2021

Features Davon's essay, "My Mother's Mother"

Summary

In A Harp in the Stars, Randon Billings Noble has collected lyric essays written in four different forms—flash, segmented, braided, and hermit crab—from a range of diverse writers. The collection also includes a section of craft essays—lyric essays about lyric essays. And because lyric essays can be so difficult to pin down, each contributor has supplemented their work with a short meditation on this boundary-breaking form.

Excerpt from Davon's essay, "My Mother's Mother"

"But when I imagine my mother’s mother, all I can see is her tying an apron around her waist, and there is a dark smudge in the middle, like how some old White crowds stood watching the swinging knot around someone’s neck that my mother’s mother knew. And yet still, she soaked her hands—wrinkled and wet—the brined black leather in the blinking soap suds, washing china and other plates from other places she would never go. And so what if she lumbered, and she stretched, and she cleaned, and wiped her tired brow because her shackled wrists could earn only enough change for the backseat ride on the bus back home?

And while cleaning those houses, polishing wood and dusting corners, she and the many other Black women she knew reminisced about some old promises. Someone long ago said that they’d all get a mule and forty acres. And the promise lingered—the notion that one day things would be better—that they’d finally have a leg up—start fresh, start new—endless possibilities. And this even motivated some of those women to scrub harder—dig deep into their souls, but my mother’s mother would say—.you’re promised nothing but your first name. Maybe she was a pessimist—or maybe she just really considered things, like lineage. She considered how they used to be slaves, all of them, with no saving accounts, no trust funds, no land, no family money; rather, they were unshackled in 1865, and kicked in the ass--get, their masters said. And they got going, with some scraps of skin still on their backs.

Then again, that’s just one chapter in the story, one narrative that belongs to a part of her, but not all of her. And it’s important for me to tell you that her life is not to be defined by all that struggle. That there was beauty in her body and skin before it was bent and broken and blackened—that her “skin was just skin before. And maybe there’s irony in all of this, thinking back on her childhood, the whole southern home, her living life normal:breakfast at seven, lemonade, Sunday school, and the way love smelled like butter and bread around a dinner table. And I’m so ashamed by how surprised that makes me feel. How hard it is to imagine my mother’s mother first and her color second. How it’s so much quicker to assume what it meant to be her was what it meant to be Black, and nothing else—.with no separation. Maybe it’s instinctual to take on her narrative and tell you those prerequisite hardships: about inequality, discrimination, and what it might have meant to be Black back then. But to be honest, I don’t know; she never told me. I just know her name, and her face, and the way she could tell me the past as if it were yesterday.”

The Harp in the Stars, an Anthology of Lyric Essays

Edited by Randon Billings Noble

University of Nebraska Press, October 2021

Features Davon's essay, "My Mother's Mother"

Summary

In A Harp in the Stars, Randon Billings Noble has collected lyric essays written in four different forms—flash, segmented, braided, and hermit crab—from a range of diverse writers. The collection also includes a section of craft essays—lyric essays about lyric essays. And because lyric essays can be so difficult to pin down, each contributor has supplemented their work with a short meditation on this boundary-breaking form.

Excerpt from Davon's essay, "My Mother's Mother"

"But when I imagine my mother’s mother, all I can see is her tying an apron around her waist, and there is a dark smudge in the middle, like how some old White crowds stood watching the swinging knot around someone’s neck that my mother’s mother knew. And yet still, she soaked her hands—wrinkled and wet—the brined black leather in the blinking soap suds, washing china and other plates from other places she would never go. And so what if she lumbered, and she stretched, and she cleaned, and wiped her tired brow because her shackled wrists could earn only enough change for the backseat ride on the bus back home?

And while cleaning those houses, polishing wood and dusting corners, she and the many other Black women she knew reminisced about some old promises. Someone long ago said that they’d all get a mule and forty acres. And the promise lingered—the notion that one day things would be better—that they’d finally have a leg up—start fresh, start new—endless possibilities. And this even motivated some of those women to scrub harder—dig deep into their souls, but my mother’s mother would say—.you’re promised nothing but your first name. Maybe she was a pessimist—or maybe she just really considered things, like lineage. She considered how they used to be slaves, all of them, with no saving accounts, no trust funds, no land, no family money; rather, they were unshackled in 1865, and kicked in the ass--get, their masters said. And they got going, with some scraps of skin still on their backs.

Then again, that’s just one chapter in the story, one narrative that belongs to a part of her, but not all of her. And it’s important for me to tell you that her life is not to be defined by all that struggle. That there was beauty in her body and skin before it was bent and broken and blackened—that her “skin was just skin before. And maybe there’s irony in all of this, thinking back on her childhood, the whole southern home, her living life normal:breakfast at seven, lemonade, Sunday school, and the way love smelled like butter and bread around a dinner table. And I’m so ashamed by how surprised that makes me feel. How hard it is to imagine my mother’s mother first and her color second. How it’s so much quicker to assume what it meant to be her was what it meant to be Black, and nothing else—.with no separation. Maybe it’s instinctual to take on her narrative and tell you those prerequisite hardships: about inequality, discrimination, and what it might have meant to be Black back then. But to be honest, I don’t know; she never told me. I just know her name, and her face, and the way she could tell me the past as if it were yesterday.”